In an immigrant community in Hayward, California, promotores knock on doors, sharing information about COVID-19 vaccines.

The promotores (Spanish for community health workers) are volunteers from the Tiburcio Vasquez Health Center, one of eight community health centers in the Alameda Health Consortium. Last year, the volunteers, mostly women, visited roughly 1,000 households a month in the Bay Area suburb and spoke outside churches and grocery stores. The outreach efforts have continued this year, and they’re highly effective. Since February 2021, Tiburcio Vasquez has vaccinated over 85,000 patients, 43% of them Latino.

Similar success stories have occurred across the country. U.S. community health centers have vaccinated 19.2 million people in the United States, and 68% of those are people of color, including immigrants, the Health Resources and Services Administration notes. And yet many immigrants — particularly those who are living in the United States without legal documentation — continue to avoid vaccinations. In May 2021, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) reported that only 31% of “potentially undocumented” Hispanic adults had received one of the vaccines, and the numbers remain low among many immigrant groups, organizations such as the National Immigration Law Center (NILC) report.

“There’s a lot of fear and mistrust particularly around the handling of personal identification and information,” says Eddie Carmona, campaigns director for the NILC. “Some folks worry they’ll be asked to provide ID that they don’t have access to, or other information that would put their status or application at risk. We all need to get out the word that people don’t need to provide their Social Security number or state-issued ID to get the vaccine, and that the vaccine is safe for immigrant families to access.”

NILC points to lingering anxieties from the Trump administration’s public charge rule, which denied visas or green cards to immigrants who would likely need future government benefits. The Biden administration ended the policy in March 2021, but the ripple effects continue.

The rule “created a pronounced and persistent ‘chilling effect,’” according to a spokesperson from the PIF campaign launched by the NILC and 14 other organizations. It led some immigrants to disenroll from health, nutrition, and economic support programs, says Carmona, because they worried that applying for public assistance would jeopardize their immigration status. In a December 2021 Protecting Immigrant Families (PIF) survey, three out of four migrant families said they were unaware that the public charge rule had been overturned.

“The policy did a lot of damage,” says Carmona. “We have a lot of work to do to build back trust and ensure that people know that they can get vaccinated without putting their immigration status at risk.”

The obstacles, however, extend beyond the rule. Some immigrants don’t realize that the vaccine is free. Roughly 75% of immigrants in the U.S. workforce have essential service jobs, Carmona says, which can increase their risk of infection, while inflexible hours make it difficult to get vaccinated.

“Our community members work in the service industry, and they don’t get paid time off,” says Drea Chavez, Tiburcio Vasquez’s marketing and advocacy manager. “If they don’t go to work, they don’t get paid. We were one of the hardest hit communities in the country.”

Many people living in the U.S. undocumented worry that government officials will target vaccination sites or health centers, even though the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement “will not conduct enforcement operations at or near vaccine distribution sites or clinics,” according to a statement from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Some are afraid to share personal information and ID requests have deterred many from getting vaccinated, multiple organizations note. In the May 2021 KFF report, 56% of vaccinated Hispanic adults said they were asked to provide a government-issued ID. Pharmacies and other sites have turned away immigrants who fail to provide ID such as driver’s licenses and health insurance cards, The Washington Post reported in 2021. Yet as Carmona notes, there is no state or federal requirement to check ID or Social Security numbers.

Language barriers can also create difficulties.

But receiving language interpretation and translation services isn’t just a courtesy, Carmona says. It’s a right. In May 2020, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office for Civil Rights issued a bulletin noting that health care providers must take reasonable steps — such as providing interpreters and written translations of documents — to serve those with limited English proficiency.

“Folks who have limited English proficiency have access to interpretation and translation services on COVID-19 vaccines under their civil rights protections,” he says.

Some companies, nonprofits, and government agencies are providing multilingual information to help the vaccine effort. CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart have posted pages in Spanish to help people make vaccine appointments, and federal agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Food and Drug Administration have produced multilingual online guides.

Most states have also posted online COVID-19 information in multiple languages. Massachusetts, for example, offers a page of multilingual COVID-19 resources on its website. The site includes COVID-19 videos in 11 languages produced by the Vermont Department of Health and Community Partners. The National Asian Pacific Center on Aging offers a vaccine helpline in eight languages and has compiled a list of each state’s vaccine webpage on its vaccine page.

Some state health departments are working with local communities to encourage vaccinations. The Virginia Department of Health has strategically targeted immigrants, not only through information campaigns, but by establishing vaccination sites in neighborhoods and apartment complexes with large immigrant populations . The agency has also recruited volunteers from within those communities to bridge language barriers and help with contact tracing, and has worked closely with community leaders such as Hispanic pastors to counter misinformation and promote the vaccines’ effectiveness.

“That was very effective because the message came from a trusted leader, not from an outside source,” says Augustine W. Doe, acting director of the Department of Health’s Division of Multicultural Health and Community Engagement. “The message then spreads by word of mouth and that creates more trust.”

Engagement efforts are also happening on a local level. In Maricopa County, Arizona, the Department of Public Health has hosted events with translators who help attendees fill out paperwork and understand consent forms. In 2021, the county worked with the Arizona Korean Nurses Association to vaccinate roughly 500 people in Mesa at the AZ International Marketplace, a grocery store that sells Asian and international food. The agency has also established phone lines so residents can ask questions in multiple languages, offered vaccines at community sites from parks to schools, and deployed mobile clinics,(including a partnership with local farms so workers can get vaccines and boosters at their worksites.

That same flexibility has worked for the Tiburcio Vasquez Health Center. The center has given shots at schools, churches, and Saturday pop-up clinics for people who couldn’t leave work during the week.

“Every time we were outreaching to small businesses and asking if they needed help with vaccination, a lot of the workers said they couldn’t find time to get vaccinated, because they either get out of work late or start really early,” says Sandra Rodriguez, the health center’s senior manager of community outreach and advocacy and leader of the promotores program. “So that led us to do weekend pop-ups. And we’ve seen more and more people getting vaccinated.”

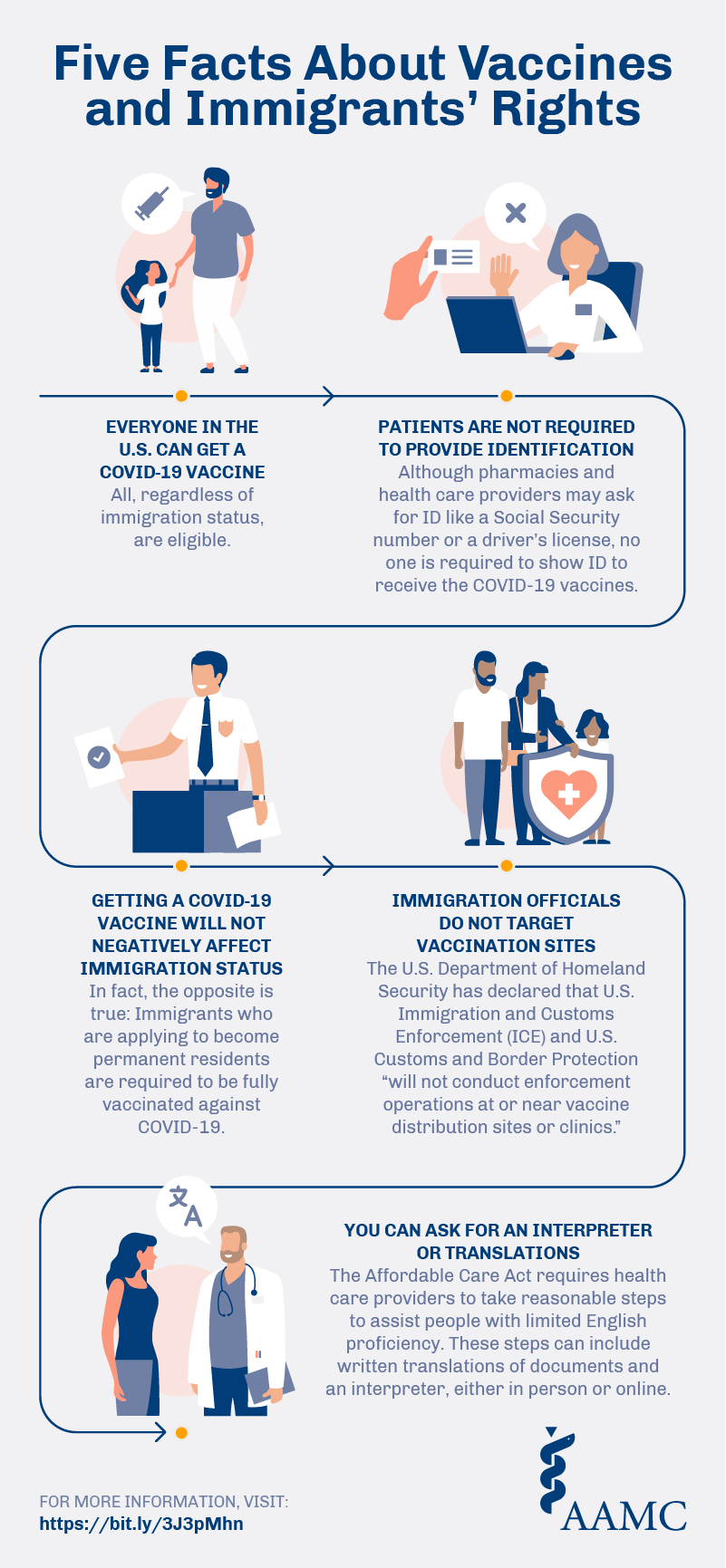

Below are downloadable infographics in Spanish and English that provide 5 facts about Vaccines and Immigrants' Rights. Anyone is welcome to download and use these infographics as needed.

Five Facts About Vaccines and Immigrants' Rights (English)

Five Facts About Vaccines and Immigrants' Rights (Spanish)