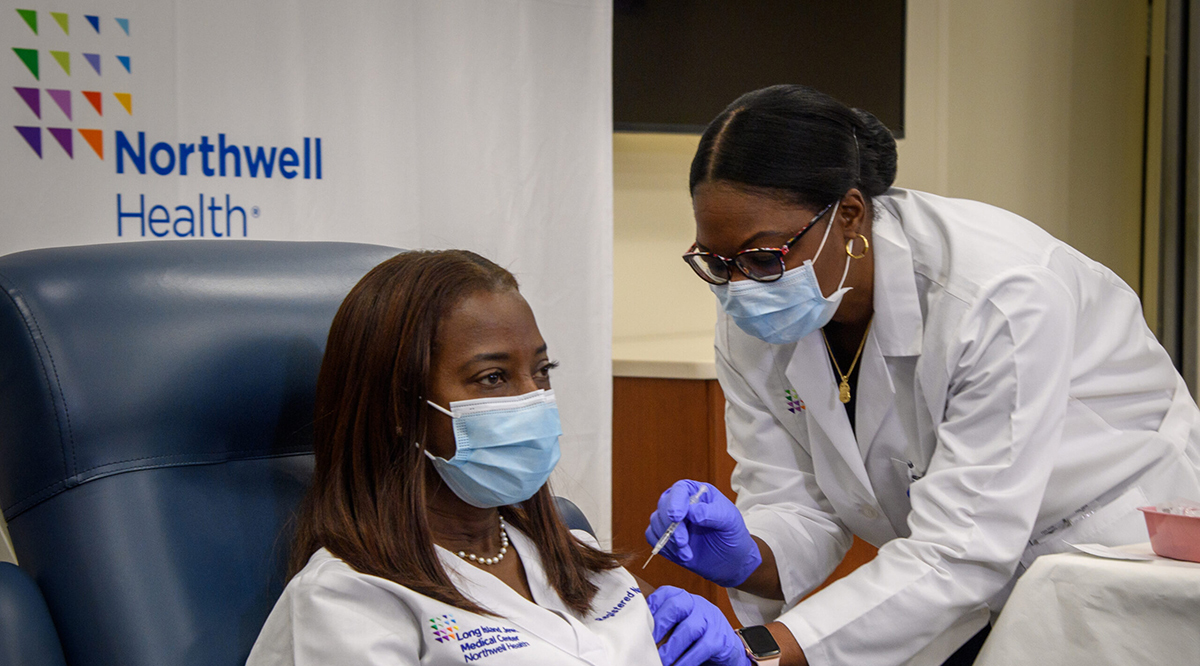

When the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History began collecting COVID-19 artifacts in 2021, it received three items from Sandra Lindsay: Her vaccination card, her ID badge, and her scrubs. Lindsay is an intensive care nurse and the director of critical care nursing with Northwell Health in Long Island, and she holds a heroic place in the pandemic’s history. On December 14, 2020, the 52-year-old Jamaican immigrant became the first person in the United States to receive a COVID vaccine in a non-trial setting.

It seems fitting that a nurse would be the first recipient. Nursing is the nation’s most trusted profession, a position it’s held for 19 straight years in an annual Gallup poll. That high esteem helps nurses to educate patients, the public, and their peers about the vaccines’ safety and effectiveness.

“Patients take to heart a lot of what we do and say, so it’s important for more of us to be vaccinated and hit the 100% mark or as close as possible,” says Mamie Williams, MPH, MSN, FNP-BC, director of nurse safety and well-being at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Eighty-eight percent of nurses have been vaccinated or plan to be vaccinated, according to an August survey from the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the American Nurses Foundation (ANF), while 4% are undecided. But 7% say they will not get vaccinated — and they’re often outspoken about their objections. In August, about 20 people, most of them nurses, rallied outside the Winchester Medical Center in Virginia, protesting the hospital’s COVID-19 vaccine mandate. Similar demonstrations have occurred at hospitals nationwide. In Georgia, a surgical technologist was fired after comparing Wellstar Healthcare System’s vaccine mandate to the Holocaust on TikTok. Ballad Health, which operates 21 hospitals and other facilities in Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, decided against a vaccine mandate for health care workers after estimating it would lose 15% of its nursing staff.

Their refusals can be fatal. In August, a pregnant, unvaccinated nurse died from COVID-19 in Alabama. She had been worried that the vaccines would harm her unborn daughter. In California, an unvaccinated nurse died from COVID-19 after giving birth to her fifth child.

Medical workers may seem unlikely to have vaccine hesitancy, but nurses are influenced by some of the same forces — geography, politics, misinformation — that affect other Americans. The nursing profession is also diverse, and everything from socio-economic status to education can affect a nurse’s views. In an October 2020 ANA/ANF survey, nurses with longer education requirements were more likely to say they would voluntarily get vaccinated if their employers didn’t require it.

“Within nursing, there is a distinction on who’s getting vaccinated,” says Williams. “If you look at advanced practice nurses, their numbers are really similar to physicians, whereas LPNs and some of the associate degree RNs have lower numbers.”

Despite the differences, ANA president Ernest J. Grant, PhD, RN, believes that up to 95% of nurses will eventually be vaccinated, pointing to mandates, information campaigns, and recent FDA approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

“It would be wonderful to get to 100%,” says Grant. “But I think around 95%-97% is achievable.”

Combatting misinformation

When nurses say they’re concerned about getting a COVID vaccine, Melody Butler, BSN, RN, understands. In 2009, she felt the same way about the H1N1 vaccine. An infection preventionist in Long Island who previously worked in pediatric nursing, Butler was pregnant — and worried.

“I was looking online for information about this brand-new vaccine and what I found was scary. It was saying, if you get this vaccine, you’ll have a miscarriage,” she says.

The health sites she visited seemed legitimate. Then she spoke with a pediatric clinical nurse educator who quickly debunked them. Many of those who wrote the articles turned out to not be medical doctors but were instead credentialed as nutritionists or chiropractors. Those who were medical doctors often had little or no experience with vaccines. Some stories cited outdated studies or even published falsehoods. The clinical nurse educator referred her to studies and information from the CDC and other legitimate sources.

Butler eventually founded a nonprofit, Nurses Who Vaccinate, which educates nurses and the public alike on vaccines. As her experience shows, even medical professionals can be duped by misinformation, especially on social media. But nurses are also well-equipped to counter false information.

“We’re trying to encourage nurses to be more vocal, maybe on their social media pages, maybe at their workplace speaking up during a lunch break or just ending a conversation when people are spreading misinformation,” Butler says.

A variety of sites can help nurses share the facts. The ANA and ANF worked with 20 organizations to create COVID Vaccine Facts for Nurses, a Johnson & Johnson-sponsored site that provides resources ranging from webinars to answers to common questions. The ANA also offers a COVID-19 Resource Center for nurses and the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium (NNCC) has developed a COVID Vaccine Toolkit with a variety of creative tools, including downloadable vaccine facts to share on social media and a timeline showing that the COVID-19 vaccines were not developed in just one year (the first mRNA vaccine research was published in 1994).

Because nursing remains a predominantly female career — 85% of the nation’s 2.4 million registered nurses are women, according to the U.S. Census Bureau — many health care systems and organizations are focusing on fears that the vaccine will diminish fertility or interfere with pregnancy. Some have asked pediatricians and OB-GYNs to address staff concerns. Butler points nurses to the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, which provides a variety of COVID-19 resources, including information on pregnancies. In soon-to-be released results of an NNCC survey, participants ranked fertility, pregnancy, and breastfeeding as areas where nurses should most focus their educational efforts.

“It’s the biggest concern we hear,” Grant says. “And it’s not true. There’s been no study that has shown that any of the vaccines interfere with fertility.”

Increasing mandates, protecting patients

In July, the ANA joined about 50 other medical organizations in announcing its support for vaccine mandates for nurses and other health care workers. Roughly 1,850 of the nation’s 6,090 hospitals have enacted vaccine mandates, and in ANA/ANF surveys, 58% of nurses expressed their support. But some nurses — after more than a year of working long hours, caring for thousands of COVID patients, and enduring personal protective equipment shortages, stress, and other challenges — resent that vaccine mandates could cause them to lose their jobs.

“Some nurses are saying, ‘We’ve been on the front line fighting this pandemic and now you’re willing to fire us?’” says Mesha Jones, BSN, RN, of University of Virginia (UVA) Health.

Employers need to understand the emotions involved and listen to nurses before implementing a mandate, says Kristine Gonnella, NNCC’s senior director of strategic initiatives. Such engagement, she believes, will boost buy-in rates for mandates.

“When people take the time to listen to frontline staff, to have a conversation about the vaccine and some of the trauma [nurses] have experienced, I think that’s often a much more successful process than immediately mandating the vaccine,” says Gonnella. “We often overlook that critical step of engaging our workforce to develop buy-in, so that their voices are heard.”

The UVA Health system’s mandate will take effect on November 1, but the organization offers an ambassador program for staff to call and ask questions about the vaccines and it sends related information to employees almost daily. Jones has spoken with one nurse who’s changed her mind, but others have said they’ll resign rather than get vaccinated.

Williams calls such objectors the “no” group: Nurses who can’t be persuaded, regardless of the evidence. But what about their patients? Do nurses have an ethical obligation to get vaccinated? Many say yes.

“I view it as a moral and ethical and professional tragedy that nurses who are eligible to get this very safe vaccine would elect not to,” says Tener Goodwin Veenema, PhD, MPH, RN, a contributing scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and a professor of nursing and public health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “They risk their own lives and those of their patients and families.”

Butler takes a similar view: “If you’re going to opt out of getting that vaccine, you’re placing more people at risk whether you realize it or not.”

Unvaccinated nurses may also be increasing workplace tensions. Responding to the NNCC’s survey, nurses said they struggle to deal with unvaccinated colleagues more than unvaccinated patients.

“That tends to have more of an impact on their mental health,” says Gonnella. “But we need to keep the lines of communication open and hopefully lead [skeptical nurses] to get vaccinated. It takes a lot of patience.”

Nurses are role models

When Grant talks to unvaccinated nurses, he listens to their concerns and points them to evidence-based information. But he also offers a potent example of his own confidence in the vaccine: Himself. Grant participated in the clinical trials for the Moderna vaccine.

“People say, ‘Wow, you participated in the clinical trials while they were still gathering data.’ And nothing has happened to me. That can be an assurance that the vaccines are safe.”

Despite concerns about nurses who remain unvaccinated, far more nurses are serving as positive role models for colleagues and patients. In the August ANA/ANF survey, 87% of nurses said they encourage the public to follow the guidance of public health officials.

“We expect nurses to model the same behavior that we expect the public to,” says Grant.

As Jones puts it, “If we’re not trusting the vaccine, how are our patients and the world going to trust the vaccine?”